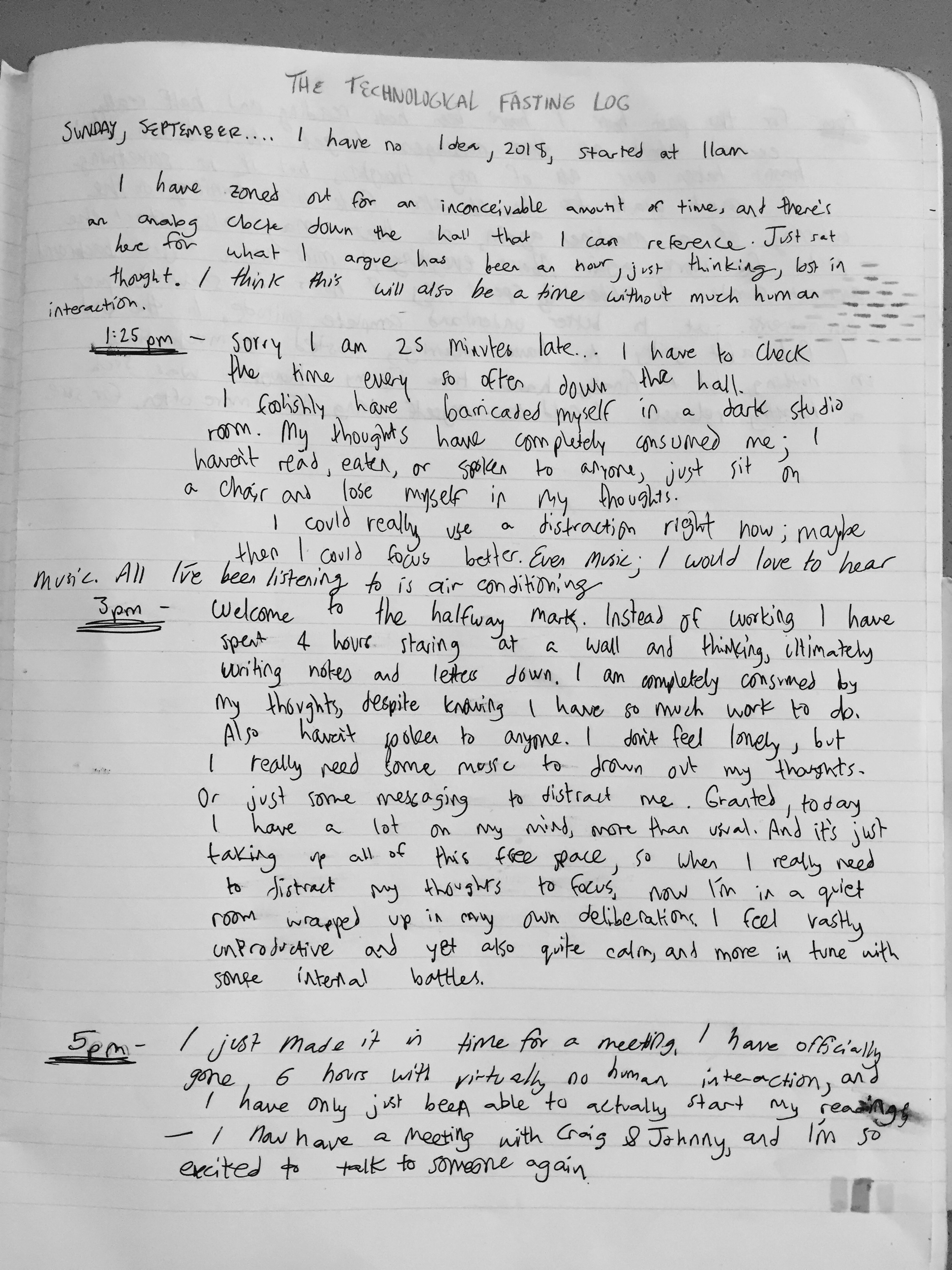

I may have taken a more extreme approach to the 8-hour technology cleanse by also removing any form of contact to other people for the first 6 hours, and not working in any environments with music or people. Much like Turkle’s analogy to Thoreau’s first of four chairs (46), I chose to spend the time without technology to be with my own thoughts.

I have to note that perhaps on a very very normal day, I would have likely also preferred electroshocks to complete boredom when sitting alone in my quiet studio (Turkle 10). Yet in the past weekend I had several different crises I needed to mull over, including accepting a new position as a senior on campus and understanding how to best navigate the final year in university. There were several thoughts on the back burner that I wish I had spent more time turning over in my head on the flight to campus back in early September. I had delayed several conversations with myself, and now I finally had time to give them my undivided attention.

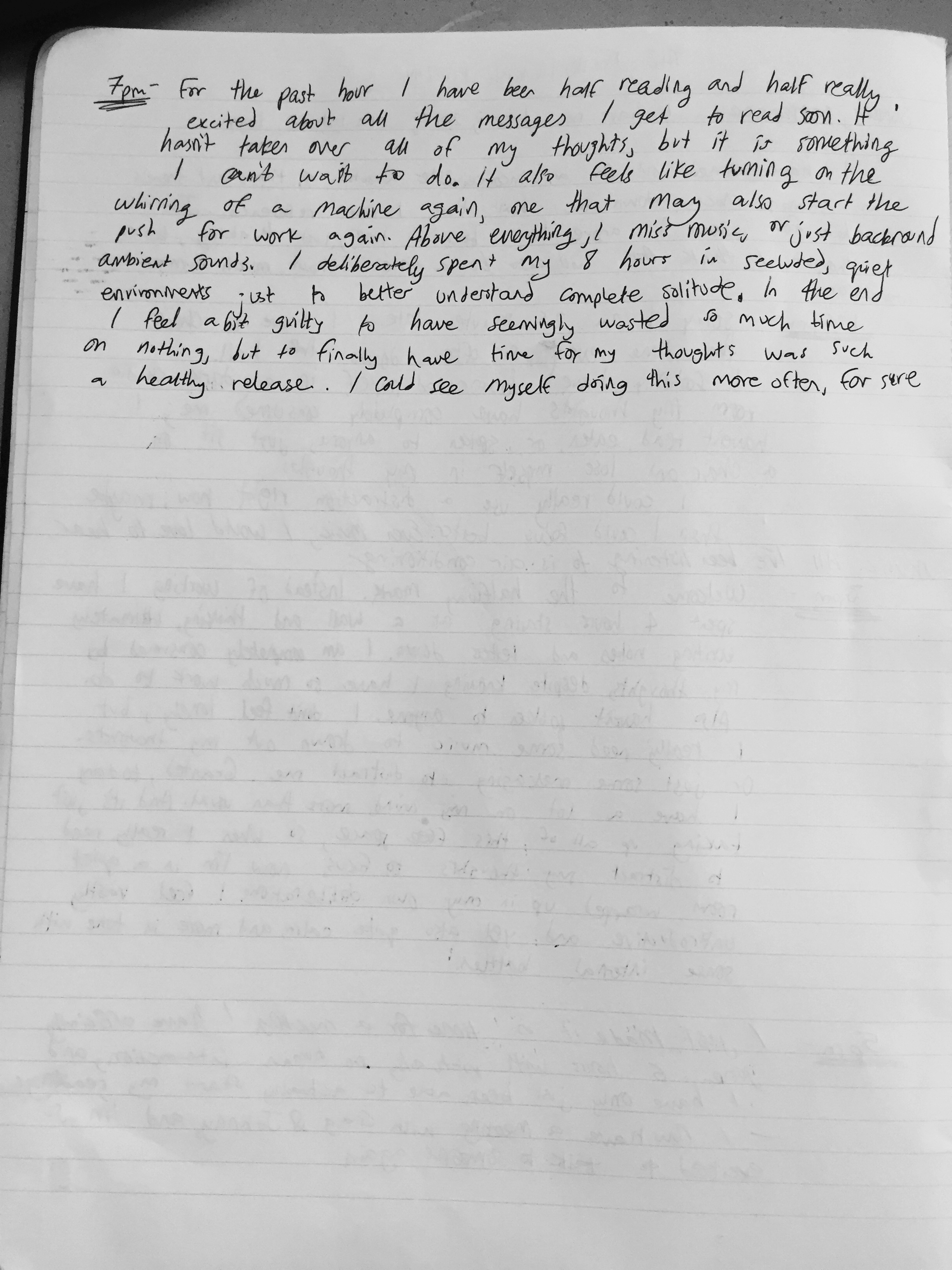

The eight hours became a time of full personal reflection and inventory. It was because of the vast number of conversations and questions in my mind that the idea of staying in a room for five hours without music or contact was actually a blessing. I began jotting down notes and webs and doodles, actually giving space to these thoughts and allowing them to unfold. I came to several resolutions and plans for the future, as well as more difficult conclusions that I needed to face.

Throughout this time, and as seen in my journaling, I desperately needed music more than anything. I believed that any form of technological distraction could actually shift my focus back towards readings and more legitimate work. I felt a strong pang of guilt for avoiding my work, and an even stronger guilt for not being readily available to anyone that needed me.

As it turns out, a visiting friend happened to be on campus, and I missed meeting them because they contacted me at one point in the eight hours. But for the first 6 hours of no communication, I was quite okay with not speaking to anyone. I had a task at hand, and I had work to be doing, even if it wasn’t necessarily conventional. I leapt at the first chance to be alone, and took advantage of the silence instead of avoiding it.

Having reread The Machine Stops, I noted this profound sense of “being” that is completely dependent on machinery, as quoted in The Homelessness chapter: “The Machine…feeds us and clothes us and houses us; through it we speak to one another, through it we see one another, in it we have our being” (Forster). The full form of human expression in The Machine Stops world is dependent on technology for human identity and personality. The people stuck within that world believe that through their continuous schedules and lecturing they achieve spirituality. In terms of the technology cleanse, I found that I was actually avoiding several questions and conversations in my mind, and it was easy to distract myself from them through technology. I now argue that boredom may be the first feeling when entering an open space for thought, but after this boredom results in questions previously left unanswered or ignored, similar to Turkle’s observations of young children alone in the woods for a long period of time, and eventually beginning to ask questions after a few hours (26).