The Printing Press

The printing press arrived a few centuries late in the Arab world due to Ottoman declarations prohibiting it throughout the empire. This was mainly out of fear of tampering with Islamic texts and later on as censorship by the Ottoman government continuing until the 19th century. Christian and Jewish communities started using the printing press much earlier, as ways of promulgating their respective religions. This was especially present in Palestine due to its significance as a center of the three faiths. In the 19th century, the region experienced a cultural shake-up from the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire’s reforms. By the turn of the century, constitutional reforms allowing the use of the printing press led to a renaissance of Arabic literature, journalism/political activity, and the emergence of modern nationalistic tendencies across the region. This was a focal point in the region’s history, with the printing press contributing to many elements of society and consequences felt to this day. It would be interesting to explore the technology under a different context than usual: delayed and popularized at a very tumultuous time in history.

Cryptography

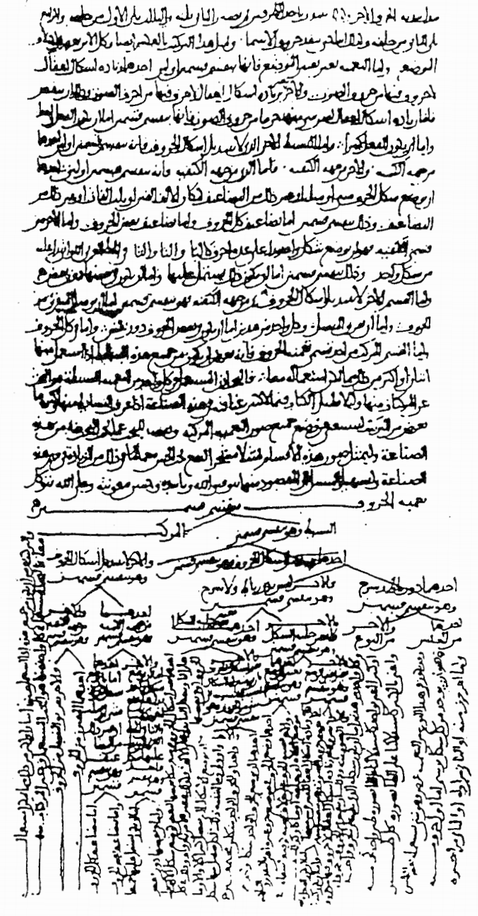

Al-Kindi was an Arab polymath living during the Islamic Golden Age in the Abbasid Caliphate. His book titled “Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages” was the first of its kind to explore methods of cryptoanalysis, and for that he is considered to be one of the fathers of cryptography. His main contribution was the Frequency Analysis, a way of decrypting substitution ciphers via the frequency of letter occurrence in a language (for example, knowing that e is the most common letter in English and substituting it for the most common letter in the ciphered text). This method proved effective in deciphering most classical texts and incentivized the rise of more complex encryption methods. This raises interesting questions about the demand for cryptoanalysis during the Golden Age and its usage in the region, since Arab scholars continued to explore the topic well beyond Al-Kindi’s manuscript was written.

Note

Since Jordan didn’t actually exist before 1921, I decided to do this assignment as a “Levantine” Arab.

My excuse: In the 19th century, Jordan was part of “Vilayet Syria” under the Ottoman Empire’s control, a division of Greater Syria. Before Ottoman rule, it was part of countless other empires and dynasties such as the Abbasid Dynasty (Islamic Golden Age). Basically, people in the area either identified as part of Syria or the Arabian Peninsula. I thought this was important to explain since the area of what is now Jordan was part of the encompassing region, not defined by its modern borders. Countries of the region share many historical, cultural, political, and lingual aspects, and the spread of communication technology in one area usually applied to others in the region.

References

“Printing History in the Arabic-Speaking World”. Yale University Library, 2009, http://exhibits.library.yale.edu/exhibits/show/arabicprinting/printing_history_arabic_world. Accessed 1 Oct 2018.

Al-Tayeb, Tariq. “Al-Kindi, Cryptography, Code Breaking and Ciphers”. Muslim Heritage, http://www.muslimheritage.com/article/al-kindi-cryptography-code-breaking-and-ciphers. Accessed 1 Oct 2018.

Najeeb, Huda. “Cryptographic Algorithms in Arabic Countries in Recent and Distant History”. Slovak University of Technology, 2010.

Suleiman, Mohammed. “Early Printing Presses in Palestine: A Historical Note”. Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 36, 2009, pp. 79-91., http://www.palestine-studies.org/sites/default/files/jq-articles/JQ%2036_Early%20Printing.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2018.