All the effort we put in was mainly to achieve one thing: Craig referencing us in his future classes, while introducing the 5th/6th/7th, etc. Annual Semaphore Competition. This, however, by no means implies our unwillingness to accept material prizes if we will be amongst the winners.

When first approaching the Semaphore challenge, we were keen to seek out a solution that was either bewildering in every means possible, or acted as a loophole around the problem (i.e. getting the message to the other person with a moving object or specimen).

By loophole, we spent the earlier days discussing the ideas of getting an object to cross the distance of the Arts Center, seeking out everything from frisbees to bow and arrows, and at one point, creating the world’s best paper airplane. With all of these methods, the risk to damage the light fixture on the ceiling was too high, or the ceiling itself was too low to allow for an object to be thrown upwards with enough room to fall back down to the partner. There were further seldom objects outside of expensive bow and arrows that could cover the distance.

(The subject of animals was thoroughly studied, however the central issue of bringing a live animal into the arts center seemed a bit too extreme, especially in being mindful of people’s allergies.

The campus cats also just didn’t comply to our training methods. Unfortunately).

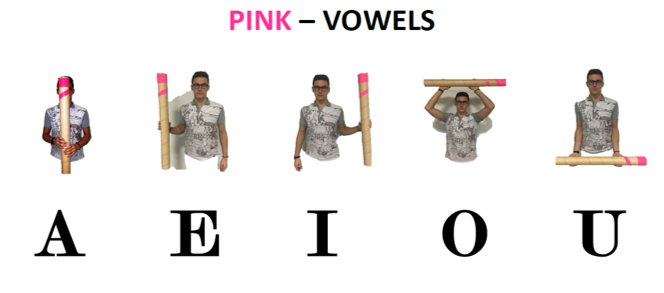

Our next game plan was to create a semaphore system so bewildering and seemingly sporadic that encryption was virtually impossible. The objective was to maintain visual and audio elements so that if either vision or hearing was compromised in a situation, there was a means to still transmit the message.

We spent a few hours sifting through materials in the fabrics room, the EDS lab, and the IM lab, eventually gathering a box of objects (known as the Super Secret Box) that either produced noise or could be thrown off of a balcony without causing casualties. Once we had achieved a list of the most random possible visual and audio things we could incorporate, we looked to defining the semaphore transmission. All the objects thrown were a part of our design meant to distract and confuse potential observers, that would be uncertain what is and what is not part of our code.

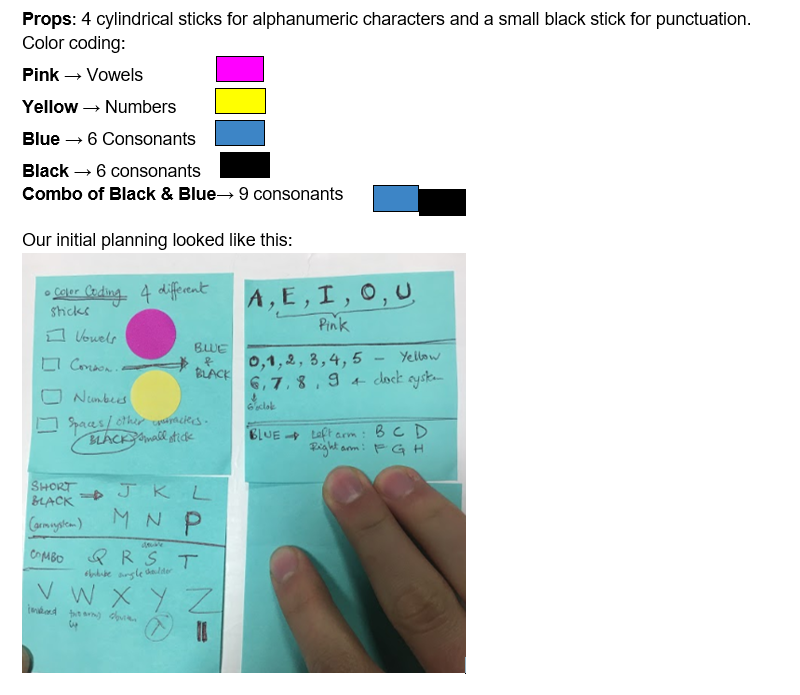

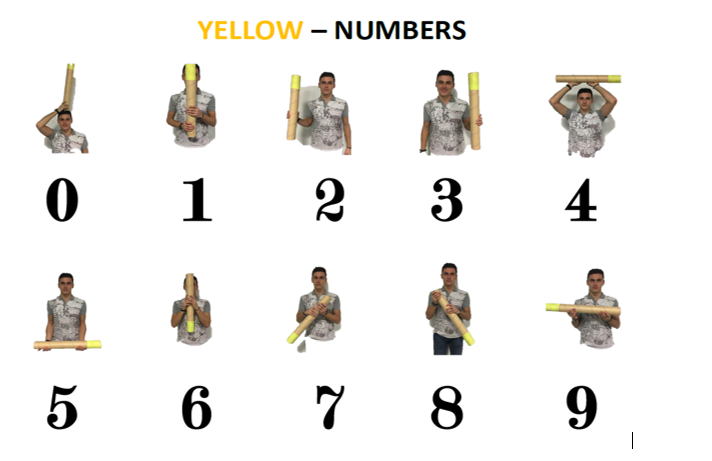

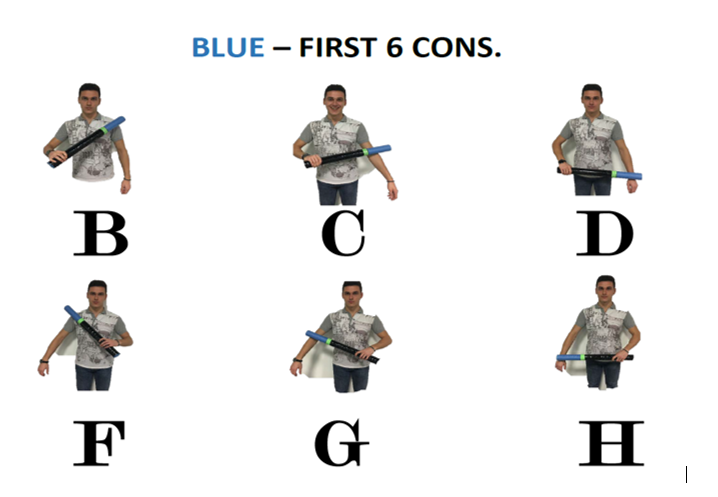

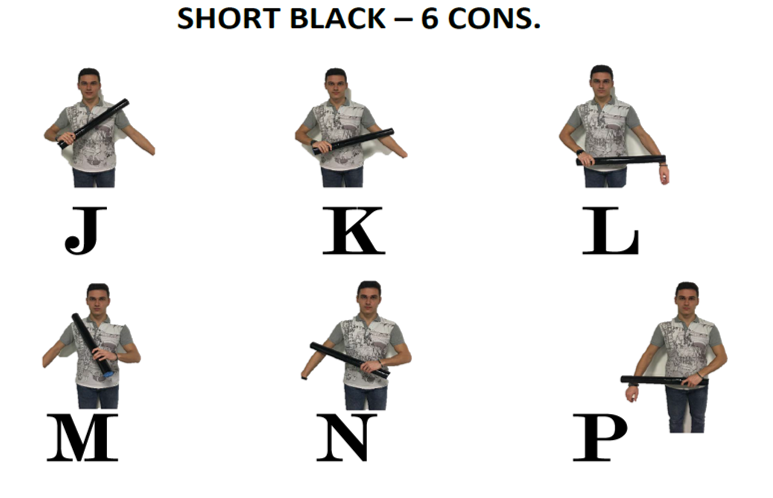

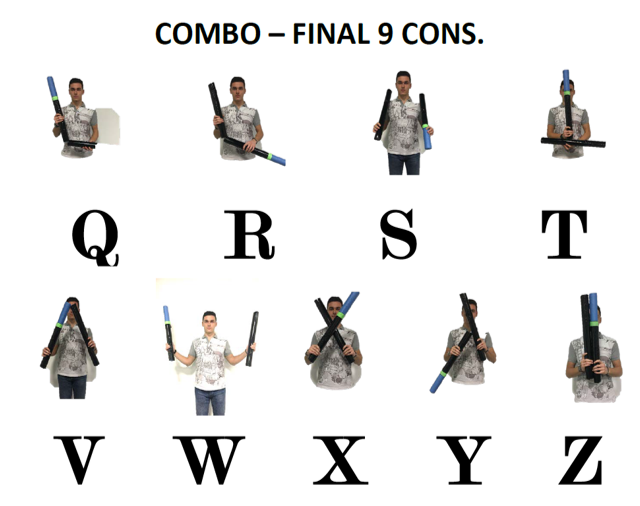

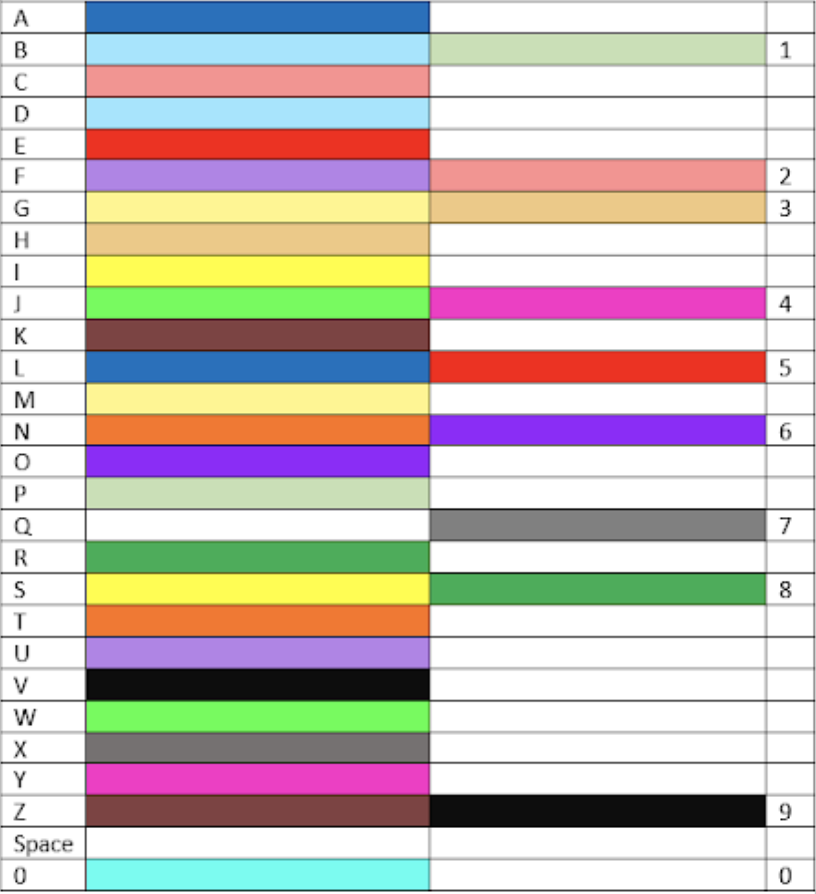

The initial idea was to divide the alphabet into a number of categories. We thought that drum beats would indicate the category, and then a series of identical movements would signifie the letter’s position in the said category, i.e. every letter in the first position, irrespective of the category would be a clap. So one drum beat, and a clap would indicate the first letter from the first category (1.1). Two drum beats and a clap would call for the letter from the second category in the first position (2.1). Eventually we settled for 4 categories, each invoked by throwing an object into a specific direction. Throwing an object up = 1st category, throwing the object down = second category, throwing the object towards majilis = 3rd category, and throwing the object toward the window = 4th category. The position of the letter in each category would be indicated by the number of drumbeats.

We used the English alphabetical order to place letters into category, in groups of first 6s and then the last category in a group of 8 letters, as we assumed that “X”, “Y”, “Z” were least used. However, we changed this as we thought that this would be easy to decode, so instead we opted for a system that placed some of the most commonly used letters of the English Alphabet in the first places of each category. This helped us make sure that it is the easier to decipher for the receiver and code for the sender.

To denote the space, we again opted for something random – brushing teeth. Having no connection whatsoever with anything else, we thought this to be the perfect indicator. For numbers, we used the whistling balloon, its sound introduced a number. To represent the number itself we used the Roman numerals up to IX. While we tried to think through most things, our matching outfits were not a part of our encoding, but rather a happy coincidence.

We also put in a place a system for checking the message in case something went wrong. We indicated the beginning and the ending of our communication through a musical sequence played on the drum sticks. If any of the words at the end were to not make sense, the receiver would not play the musical sequence, but rather use drum beats to indicate what word was not caught properly. In case the last word was missing, the receiver would beat once, if the second to last, then twice, etc. Catching this, the sender would replay the miscommunicated word.

Rehearsing

Rehearsing was soooo exciting. We used our newly created system to communicate loudly inappropriate messages in public places. Provided that we have not been expelled, so far, we believe that it can be concluded that our encoding is pretty safe.

Final Execution

Not practicing throwing objects over the balcony proved to be the greatest risk going into the Tuesday competition. Though we were able to transmit messages to each other in record times of 4:30 in rehearsal, actually throwing objects ended up taking the full 6 minutes in the final competition. Even picking up the toothbrush after every word took up precious seconds versus just the act of brushing teeth. I was further aware of the reaction being distracting when I was throwing random objects off of the ledge, but it still ended up catching me off guard and I was much less smooth in identifying a letter.

The stress of the competition and knowing what was at stake – being in the Semaphore Hall of Fame – made it definitely harder to decode. Hani and Raitis set the bar pretty high and it was nerve-wracking to go after them. We also wanted to make the most out of it, as we knew how much effort we put into preparing for this day. By the end of the time, I realised that not everything was making sense, so I tried to use the above mentioned system to check the 1st word, RABZ, unfortunately we did not have enough time to do that.

Reflections

From watching the other groups, I noted that it was far more convenient for the transmitter to have a more memorizable system so that there was no hesitation to transmit multiple letters after one another from the signal of the receiver. Choosing the bewildering method meant having an extensive sequence for transmitting a single letter: checking the category, throwing an object in the appropriate direction, checking the letter for its count, and knocking the appropriate number of times.

On the receiving side, a few times I was not sure whether the object was thrown upwards or not, I believe that this is something that can be fixed with more practice and does not represent a huge design problem. During our “performance, however, I noticed another limitation – objects falling on the floor produced a sound. As I was only watching the sender while they were throwing objects, this lead to me not being always sure how many drum beats were actually played and whether the sound produced by the falling object was just a noise or something I should consider while decoding.

Our plans to confuse the troll and use dramatic visual and audible effects for the semaphore to work in longer distances were ultimately successful. Our shortcomings in transmitting the message quickly and without any error proved to be the sacrifices when using the irregular method. It is worth saying that throwing KitKats was probably one of the better ideas, because it was the most efficient way to distract people from actually paying attention to the code.

If the procedure were to be modified, I would consider adding more categories so that the alphabet could be broken down into categories of 4-5 letters, therefore would be easier to memorize without having to continually refer to the sheet. The new categories could include dropping from both hands, throwing an object backwards, or simply raising an object over one’s head.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/FirstTelephone-58a750b23df78c345bbd2870.jpg)